The Smart Consumer's Guide to Understanding Lab Reports

Welcome to Truth Be Told, the weekly food and fitness newsletter published by The Whole Truth Foods.

Editor’s note: Arjun Anjaria and I met a few weeks ago when he was briefly visiting Bombay, and we had a long chat about lab testing and food safety, and how his team is attempting to do this rigorously through Unbox Health—a new platform for unbiased lab-tested ratings.

I learnt a lot from Arjun's experience, so when I saw his LinkedIn post critiquing the citizen-funded Protein Project that's been buzzing these last couple of weeks, I requested him to write for us. I thought his expertise could help readers understand how to make sense of lab report data. Because it is technical and not straightforward.

That's today's piece, and I think you'll find it incredibly helpful for reading numbers in the right context.

Also, I want to be upfront: The Whole Truth Foods—which publishes this newsletter—sells whey protein. As an Editor, I'm conscious about avoiding topics where there's a conflict of interest. In this case, there isn't one: our brand wasn't flagged with any concerns in the report, and this article is a constructive critique of a report that actually shows us in good light. I'm sharing this for full transparency, so you don't have to second-guess :)

And Arjun isn't connected to or endorsing TWT in any capacity. We literally just met (and couldn't even grab coffee!), and I asked him to write about lab testing! That's it!

– Samarth Bansal (samarth@thewholetruthfoods.com)

A couple of weeks back, Dr Cyriac Abby Philips (popularly known as "The Liver Doc") published a report titled "Citizens Protein Project 2".

This was the second run of the Protein Project where Dr. Philips and his team initiated lab testing of popular protein powders in the Indian market, sharing results across social media posts that promptly went viral.

The CPP2 is a citizen-funded study that tested 34 protein powders sold in India, comparing expensive “medical/pharmaceutical” protein powders prescribed to patients (with cancer, liver, kidney diseases) against regular sports/wellness protein powders that consumers buy. The study was conducted by MESH (Mission for Ethics and Science in Healthcare), a non-profit organization.

The project was crowdfunded, making it markedly more independent than most other public testing, with no obvious commercial interests involved. (All data is publicly available.)

The posts claimed several brands were under-delivering on promised protein, contained heavy metals, and showed signs of "amino spiking."

While the project resonated with increasingly wary consumers, it also sparked significant debate among industry professionals questioning the validity and significance of the findings.

As someone who leads a consumer health platform that leverages lab testing to rate food products and supplements, I see this as an important teaching moment.

Lab testing is hands-down the most effective way to evaluate product quality. In an industry filled with paid reviews and influencer vomit, it's our only source of objective truth. But most people don't realise that your assessment is only as good as your methodology and interpretation.

The Citizens Protein Project, despite its good intentions, illustrates the gap between raw data and meaningful conclusions. Let me walk you through what every consumer needs to know about reading lab reports, using real examples from both this project and our own experience.

1. Single lab results are unreliable

Food testing is far more complex than most people imagine. You can't just send a sample to one lab and treat the results as gospel. The world of atoms can be nuanced, and results are often non-deterministic in surprising ways.

Let me paint you a picture from our own operations. A few months ago, we rated several chips products at Unbox Health. We assign unique internal IDs to each sample to track data through its lifecycle. When results came back from one lab, the data for two samples looked distinctly off.

After digging deeper, we discovered the lab had completely swapped the results – Sample-ID-A's data was assigned to Sample-ID-B and vice-versa. If we hadn't been using multiple labs for cross-verification, we would have published completely wrong ratings. This could have been catastrophic.

Another time, we sent Vitamin supplements to a trusted partner lab. The results came back showing absurdly low vitamin content. Something felt wrong. On closer inspection, we found they'd reported in micrograms instead of milligrams – a 1000x difference that completely changes whether a supplement is worthless or perfectly fine. Again, using multiple labs helped us catch this error.

Perhaps most troubling was our Melatonin experiment. We took tablets from the same bottle, split them into two samples with different IDs, and sent both to the same lab. Since they're literally from the same product, the results should be nearly identical, right? Wrong. The heavy metal values came back drastically different. When confronted, the lab traced it to issues in their testing process and acknowledged the error.

These aren't isolated incidents from sketchy labs. These are from some of the most reputable testing facilities in India. Even the best labs with the highest certifications are run by humans who make mistakes. That's why at Unbox Health, we always test every product at up to 3 different labs. Yes, it increases our costs significantly, but it also means we don't have a single point of failure. And it helps us sleep better at night :)

The Citizens Protein Project relied on results from a single lab. While that doesn't invalidate their findings, it does mean we should view them with appropriate caution.

2. Legal margins exist for good reasons

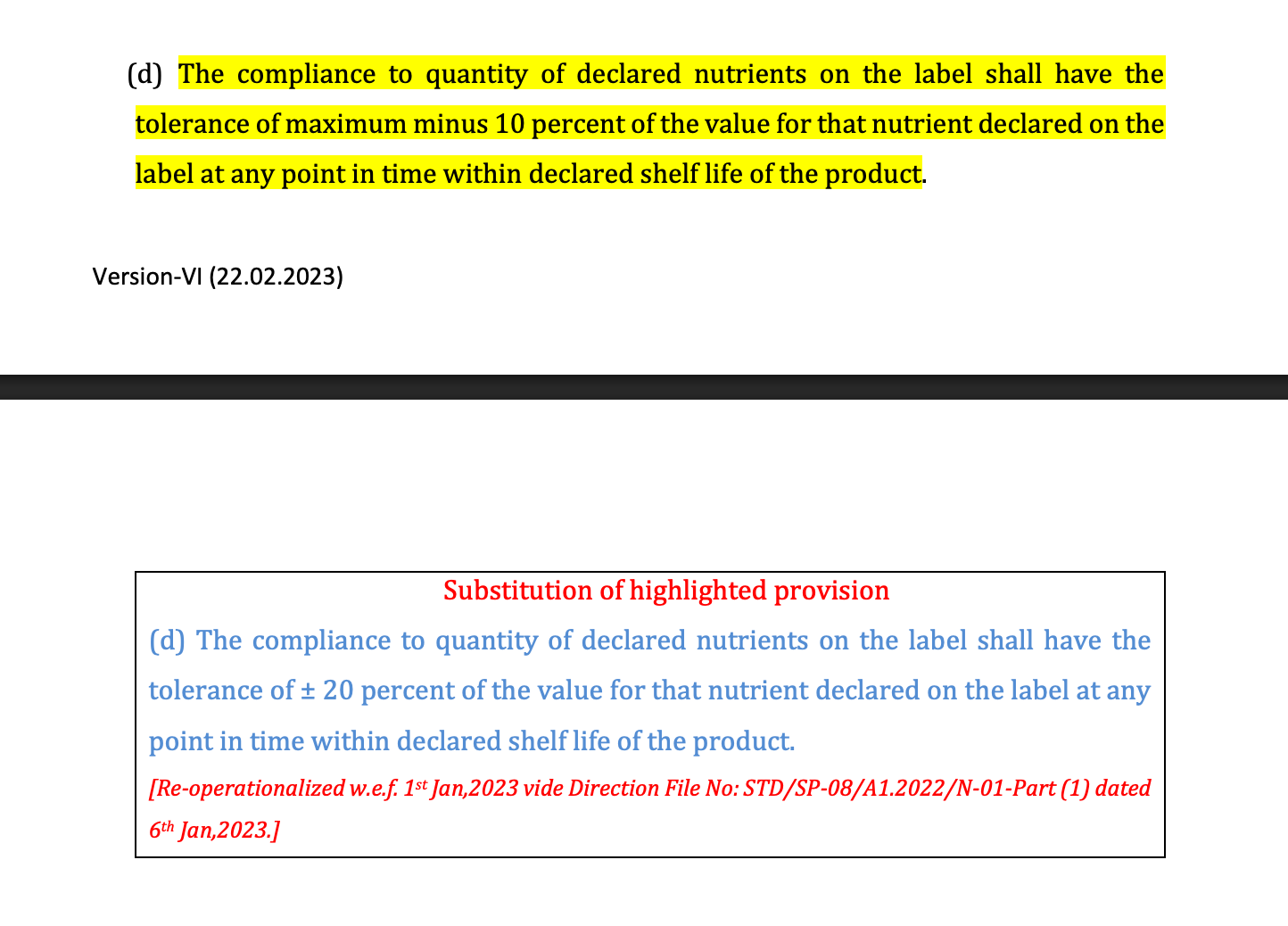

Here's a little-known regulatory detail: FSSAI legally allows a 10% deviation from label claims for protein content and other macronutrients. In fact, this tolerance has been provisionally relaxed to ±20% under the 2023 direction.

Yet this project report flagged several brands in red despite being within this margin. Which leaves out this regulatory and practical context.

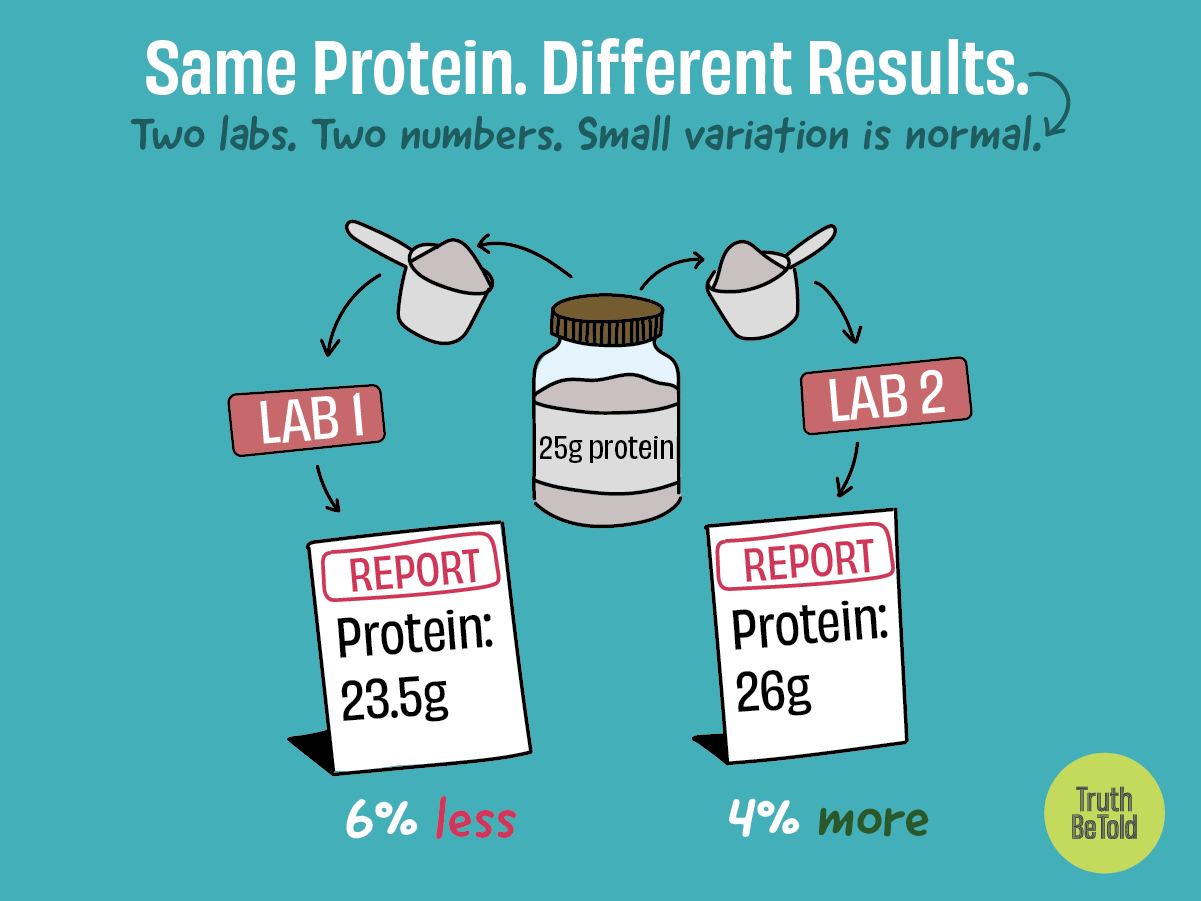

Let's make this concrete. If a protein powder claims 25g of protein per serving on its label, FSSAI allows it to contain anywhere from 22.5g to 27.5g and still be compliant. Why? Because natural variation is real. Test the same product on different days, with different moisture levels, using different samples from the same batch, and you'll get slightly different results.

One brand in the report was marked red for testing at 67% protein versus 72% on the label. In a 30g serving, that's 20.1g versus the claimed 21.6g – a difference of just 1.5g. Another was flagged for showing 82% versus 88% labelled. These deviations (6.9% and 6.8% respectively) fall well within the acceptable 10% range.

Now, when should you actually worry? If a product claims 25g protein but consistently delivers only 15g (a 40% deviation), that's a real problem. If multiple tests across different labs all show 20-30% less protein than claimed, that's likely intentional mislabeling. But a 5-7% variance? That's normal manufacturing and testing variation, which is exactly why regulations account for it.

3. "Detected" doesn't mean "dangerous"

Heavy metal contamination in food products is a serious concern. Lead affects brain development, cadmium damages kidneys, and arsenic is a known carcinogen. Testing for these contaminants is crucial, and I applaud any effort to do so.

However, the dose makes the poison—a fundamental principle in toxicology. Water can kill you if you drink too much. Table salt is lethal at high doses. So the question isn't whether something is detected—it's whether it's present at dangerous levels.

Trace contamination is unavoidable in many foods because plants absorb metals from soil and water, and animals accumulate them through their feed. That's why regulators worldwide don't require zero detection. They set clear safety thresholds for these toxins. For protein powders, these limits are: Lead (2.5ppm), Arsenic (1.1ppm), Cadmium (1.5ppm), and Mercury (1.0ppm).

The Citizens Protein Project applied a simple binary rule: detected = bad, not detected = good. This is like saying any house with bacteria is dangerous, ignoring that some level of bacteria is normal and harmless. A product showing 0.5ppm of lead isn't dangerous—it's five times below the safety limit. But without this context, "contains heavy metals!" sounds terrifying.

What happened in the report was that some products were flagged red simply for having detectable levels, regardless of whether those levels posed any actual risk.

4. Trace amounts don't equal intent

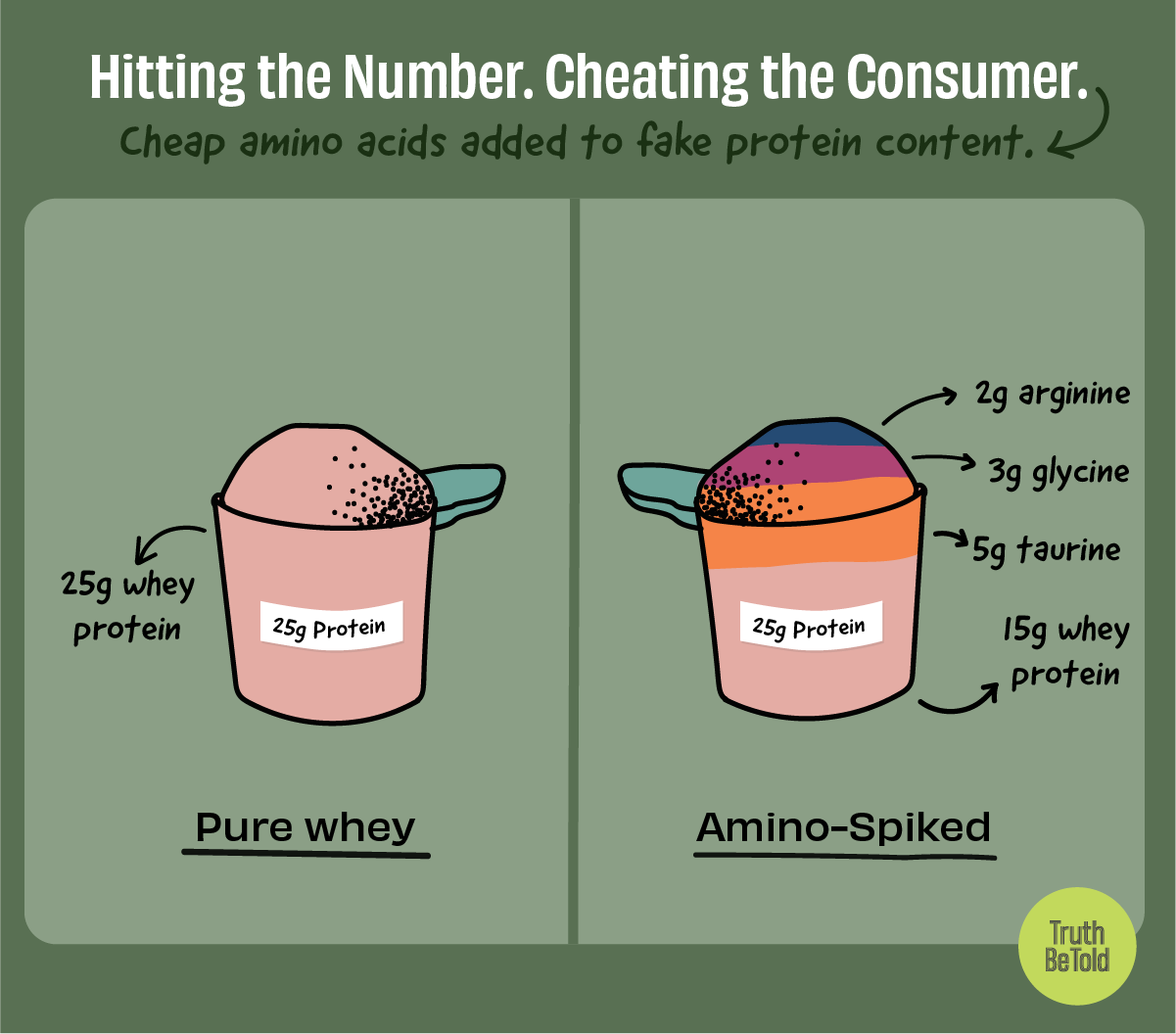

Perhaps the most serious allegation in the report was "amino spiking." This is a real problem in the supplement industry that deserves attention. Let me explain how it works.

Protein content is typically measured by testing nitrogen levels (since protein contains nitrogen). Some manufacturers exploit this by adding cheap nitrogen-containing amino acids like glycine, taurine, or creatine to their products. These spike the nitrogen readings, making it appear there's more complete protein than actually exists. It's particularly deceptive because standard testing can't distinguish between nitrogen from complete proteins (which have all essential amino acids your body needs) versus nitrogen from cheap fillers. (More details in this previous TBT article.)

This is why amino spiking is a legitimate concern that requires sophisticated testing methods beyond simple nitrogen analysis. You need amino acid profiling to detect it properly. Which the Citizens Protein Project did.

But here again, in at least two brands, they alleged amino spiking based on finding trace amounts of taurine. For example, they found 0.005% taurine in one brand and 0.087% in another. To put this in perspective, if you have a 30g serving of protein powder, 0.087% is just 0.026g of taurine – about 26 milligrams.

This doesn’t indicate amino spiking. To make economic sense, amino spiking requires adding at least 1-2% of cheap amino acids, which is around 300-600mg per serving. For significant cost savings, you'd probably need even more, around 10g of cheap aminos per serving.

While it's fair to question why any taurine is present, jumping from trace detection to suggesting deliberate fraud—without emphasising the quantities involved—can confuse consumers, especially in viral social media posts.

The Big Picture

The Citizens Protein Project deserves credit for attempting to bring transparency to an opaque industry. Public-interest testing is valuable, and MESH’s intent to protect consumers is commendable. However, the project's impact could have been stronger with a clearer and contextual interpretation of the data.

When we share lab results publicly, we have a responsibility to help people understand what the numbers actually mean. Otherwise, we risk causing unnecessary panic or, worse, teaching consumers to dismiss all testing as unreliable.

We need more citizen science—done rigorously and communicated responsibly. Your health decisions deserve nothing less.

Next time you see lab results online, run this quick check:

1) Look for multiple data points: Single lab results can be wrong. Look for testing that uses multiple labs or repeated measurements.

2) Context is everything: Raw numbers mean nothing without safety thresholds and regulatory limits. A 5% deviation might be normal; a 50% deviation is likely fraud. "Detected" doesn't equal "dangerous."

3) Understand natural variation: Legal margins (like FSSAI's 10%) exist because perfect replication is impossible. Minor variations between tests are normal, not evidence of fraud.

4) Proportionality matters: Trace amounts (0.00X%) are usually meaningless for fraud allegations. Consider whether findings make economic sense (would anyone spike with 0.005% taurine?).

PS: Here is a short feedback form to help us understand how we're doing. Would you please share your thoughts? Link here. Thank you!

This is so good! Thank you for simplifying sensational claims for a layperson like myself. I’ve just learned a whole lot!